The Gendarmerie

The Hungarian authorities undoubtedly bear responsibility for the destruction of two-thirds of Hungarian Jewry. Without the enthusiastic operation of the gendarmerie, the police and the public administration directed by the government collaborating with the invaders, the Nazis would not have been able to deport 430,000 people to Auschwitz in just a matter of weeks. The implementation of the anti-Jewish decrees, the ghettoisation and deportation generally were carried out with the utmost cruelty of the authorities. The gendarmerie treated the Jews especially brutally.

In the summer of 1944 the commander of the Hungarian gendarmerie, Lieutenant General Gábor Faragho, was most pleased with the conduct of his units. In his opinion, of the more than 20,000 men participating in the nationwide operation only a few behaved in reprehensible manner, and "we must take this as equal to zero".[1] Survivors' eye-witness accounts directly contradict his statement; it is the number of decent gendarmes whose numbers "must be taken as equal to zero".

In particular, gendarmes who served in larger collection camps and deportation centres under the command of so-called

Words of the survivors - link center"Move on you filthy Jews, you won't come back here anyway" They conducted electric currents into the women's wombs |

The conduct of the Hungarian Gendarmerie performing the "dejewification" of Hungary was unusually violent, even compared to similar organizations operating in other countries. This caught the attention even of the Germans, prompting Eichmann to make the following cynical remark: "In some cases my men were shocked by the inhumanity of the Hungarian police" [i.e., gendarmerie, as Eichmann made no distinction between the two organisations].

|

SS Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann the German officer who directed the deportation of Hungarian Jews. |

Instead of being an isolated event, the brutality of the gendarmerie was widespread and widely known. At a meeting between Döme Sztójay, the prime minister of the collaborating government and Papal Nuncio Angelo Rotta, the latter raised his concerns primarily for converted Jews, but he also took Sztójay to task for the "brutal and degrading" methods used by the gendarmerie during the deportations.[4] The bishop of Csanád, Endre Hamvas, asked Archbishop Jusztinián Serédi to call Sztójay's attention to the "outrageous measures" he had witnessed personally. Reacting to a previous comment by Sztójay, Hamvas wrote the following:[5] "The Prime Minister considers as exaggerated reports of cruel and ruthless conduct. But how could the expulsion from one's home, the robbing of the last pieces of jewellery and wedding rings, the crowding of 70 to 75 people into cattle cars locked for 4-5 days without food and water be done without cruelty?"[6]

In an ordinance dated in early June Regent Miklós Horthy asked Sztójay to relieve State Secretaries of the Ministry of the Interior László Endre

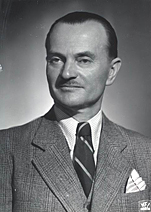

|

State Secretary of the Ministry of the Interior László Endre, Hungarian leader of the "dejewification" |

Gendarmes as reflected in the DEGOB protocols - ghettoisation and deportation

The events reported to Eichmann, Wisliceny, Rotta, Hamvas and Horthy had to be personally experienced by Hungarian Jews.

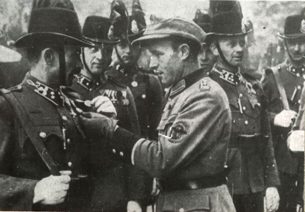

|

Hungarian Gendarmes making friends with a German soldier |

Hungarian Jews had negative experiences with the gendarmerie even before the German occupation . However, these examples are less frequent; atrocities against the Jews became more prevalent following the 1944 German occupation of Hungary. In Perecseny Jews denounced by the village notary were led away by gendarmes and "they came home beaten to a pulp".[11] In Beresova Jews circulating without the yellow star "were caught by the gendarmes [who] beat them badly, especially the men. They entered Jewish homes where they stole, looted and took everything they could lay their hands on".[12]

Already in 1941 many Jews were taken from Ilosva at the time of the Körösmező deportations. Those that remained suffered terribly in the spring of 1944. "In 1944, following the arrival of the Germans, the Hungarian gendarmes were extremely cruel with the Jews, who did not dare walk on the streets."[13]

J. B. from Kövesdliget had similar experiences. "... Following the arrival of the Germans the Jews were subject to constant harassment. They broke the windows, we were scared to leave the house, because the gendarmes beat us brutally, especially the men."[14]

Again, a girl from another village in Carpatho-Ruthenia who was seventeen in 1944, remembers the one month between the German occupation and the start of the ghettoisation: "The Hungarian gendarmes entered the homes demanding cash and valuables; those who did not reveal the location of hidden valuable were severely beaten."[15]

One day the gendarmes came for B. L. in Bártháza, "I had to remove my shoes and stockings and one of them beat my bare soles with an iron saw until I bled." The gendarmes never questioned B. L., he never found out why he received the beating.[16]

But this was just the beginning: on April 16, 1944 the ghettoisation of Jews in Carpatho-Ruthenia commenced. In Huszt "the gendarmes were brutal and mean, they barely gave us any time to pack up before they herded us all into the ghetto", is how R. B. recalled April 1944 eighteen months later.[17]

Women who later thought it was important to identify their torturers were taken from Técső to the ghetto in Sátoraljaújhely: "The gendarmes who treated us in Tárkány with unimaginable viciousness were the following: non-commissioned officer Béla Németh, András Bódy, József Demeter, Domrádi (later transferred to Kassa) and Pálfalvi."[18]

The ghettoisation in Kisvárda took place under "the most horrific terror and abuse. The guard duties were discharged by gendarmes armed with truncheons who drove people to the designated area, beating men, women, old and young alike."[19]

The city of Munkács was the largest collection point of Deportation Zone I. Between

|

Entrance of one of the Munkács ghettoes |

Those crammed into the brick factory did not fare better either. According to B. I., 16 at the time, "the cruelty of the gendarmes was surpassed only by the three SS men present".[23] Lumber merchant Dezső Königsberg remembered as follows: "several people were clubbed to death by the gendarmes and SS serving in the camp ..."[24]

At the brick factory in Munkács the SS and gendarmes raped Jewish women: "The Germans and the gendarmes (the latter even more) raped young girls who then had to be taken to the hospital."[25]

Those languishing in the brick factory were deported on May 15, and the population of the ghetto was driven to take their place only to be deported in a few days.[26] "When we moved from the city ghetto to the brick factory, they drove us so hard we had to run. A soldier stood every ten steps and beat everyone as we passed. Four people died on the way. In the brick factory there was a teacher from Budapest; he was forced to sing, and the rabbis were severely beaten.[27] In their joint testimony, eleven survivors from Munkács remembered: "We were driven along the road like horses and reached the brick factory by a long detour. The ones that fell behind were shot dead and the relatives were not even allowed to look back."[28]

The situation was similar in other large ghettoes throughout the Zone (Ungvár, Nagyszőllős, Beregszász, Huszt, Iza, Técső, Sátoraljaújhely, Máramarossziget, Mátészalka, Nyíregyháza). Jews taken to these ghettoes suffered the same torture as the others in Munkács.[29]

While the DEGOB protocols do not document events as thoroughly in Deportation Zones II, III, IV, V and VI as the events in Deportation Zone I, we find a number of examples of gendarmerie brutality committed in these areas as well.

The Jewish population of northern Transylvania was swept up in the second wave of deportations. W. N., a Jewish policeman in Szatmárnémeti, managed to escape the atrocities, "but I watched in horror what the camp gendarmerie officers and the SS did to the other Jews."[30] Engine fitter Mór Grünstein recalled his days in the Szamosújvár ghetto: "The gendarmes started to interrogate, and they never stopped beating me... If they stopped one day, they resumed the next day".[31]

The testimonies below come from ghettos in northern Hungary in Deportation Zone III. H. V.'s father was a well-to-do Jew from Balassagyarmat, so the gendarmes "summoned him in the ghetto and beat him savagely during the interrogation."[32] In the ghetto in Érsekújvár "wealthy people were beaten so badly, they ended up in the hospital."[33] In the Miskolc ghetto, gendarmes "specialized" in assaulting people with a whip.[34]

Deportation Zone IV covered the area south-east of the Danube in Hungary, while deportation Zone V extended over the country's

|

Deportation of the Kőszeg Jews |

According to the original plans, Deportation Zone VI would have covered the capital and its immediate vicinity. However, alarming reports from the fronts, growing international objections and indignation, as well as the spreading news of exterminations forced Horthy to stand up to German demands at the beginning of July. With this the Regent who took the initiative again managed to stave off the deportation of the Jewish population of Budapest-at least for the time being. However, those living in the outskirts of the capital could not escape their fate: they were locked into ghettos between the end of May and the end of June and transported to deportation collection sites between June 30 and July 3. The two largest collection sites were the brick factories of Budakalász and Monor. Here again, guard duty was provided by the gendarmerie,[37] that generally behaved the same way as it did in other parts of the country.

Dr. Ilona László was sent to Budakalász from the ghetto in Újpest. "There were a lot of people crammed into the brickwork. There was no food. ... People were beaten to reveal the location of hidden valuables and jewellery."[38] Some were murdered there as well.[39] Mrs. Weisz was so traumatized by her experience at Budakalász that eighteen months later she testified: "perhaps conditions were not as horrible even at Auschwitz as they were in the brick factory at Budakalász".[40]

Conditions were similar at the Monor brick factory. Jews suffering from lack of drinking water and food were kept under constant terror by gendarmes searching for valuables. "The gendarmes tortured people with electricity; they collected and beat especially more prominent men, searching for jewellery and cash. We were at a point where we could barely wait to be put on the trains", remembered L. K.[41]

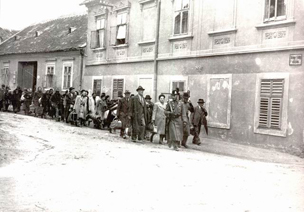

With the exception of Budapest, events unfolded in a similar pattern. The ghettoisation and concentration of the Jewish population

|

Deportation in Körmend |

Besides the torture that became routine, Jews testified that gendarmes considered the deportation process as good business and took every opportunity all the way to the Hungarian border to extort valuables (cash, jewellery and watches) from the hapless crowd. "We were taken to the station at Ilosva, we were badly beaten along the way and put in the cattle cars all covered in blood. They took off ten men from one of the cars and said if we did not give up all our jewellery we still had in our possession, the ten would be shot dead. Eventually they were returned to the cars beaten to a pulp."[42] "There were 85 of us in the car. This was bad enough, but along the way they kept threatening to shoot us if we did not hand over our jewellery." [43] "The gendarmes had to be paid for everything: to open the door for five minutes and at least one hundred pengős to get some water."[44]

Of course there were cases when people could not get water even for money; instead "[the gendarmes] threw stones at us through the small windows and in our car alone ten old people died of thirst."[45] There was no mercy when the second transport from the Munkács brick factory was loaded onto the train: "Anyone asking for water was shot on the spot".[46] Gendarmes escorting one of the transports from Békásmegyer to Auschwitz "shot into the cars twice because women were screaming for water."[47]

The Arrow Cross Era

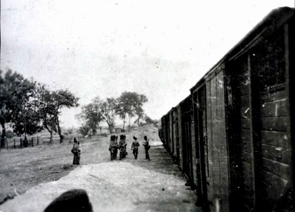

Following the Arrow Cross takeover of October 15-16, tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews were sent in

|

Deportation of the Soltvadkert Jews |

Many gendarmes serving at the Józsefváros railway station in Budapest abused deportees to get their money. Supplies on freight cars (water, food, and sanitary accommodations) continued to be inadequate, brutal treatment was routine,[48] and in some cases those attempting to escape were shot dead.[49] However, the degree of brutality seen in the countryside was rarely repeated in the capital. More typically, gendarmes tried to squeeze every penny from starving and thirsty people. "The gendarmes took large sums from us to let people go to the toilet; they took the money but they did not allow anyone to leave the car,[50] F. F. accounted later. Dr. H. A. remembered these trying times as follows: "Gendarmerie escorts took advantage of our thirst and hunger. For instance, they took watches and wedding rings for a glass of water.[51] S. F. and his companions travelled six days without food or water in the cattle car. "We paid 2-300 pengős for a pail of water and I gave my overcoat for two small slices of bread and an eighth-pound of raw salted ribs. I lived on this for six days."[52]

Jews marched to the country's western border met the same treatment seen during the summer deportations. Almost without

[53] "A gendarme called Mittelmeyer shot dead an 18-year-old girl who, exhausted by hunger, went to the house of an acquaintance to ask for food. She did not try to escape; the gendarme shot her when she returned to the column."[54] "The gendarmes treated us most horribly."[55]Gendarme boots, blows of the fist, bayonets and curses. For the majority of the murdered Hungarian Jews, these were the last memories of their homeland.

Footnotes

[1] At the June 21, 1944 Council of Ministers session, Faragho put it this way: "If we take into consideration that we had already deported 400,000 Jews to labour camps and resettlements, the fact that complaints were lodged against a few of the 20,000 gendarmes participating in the operation, we must consider the problem as equal to zero." Quoted by Braham, 1997, p. 887.

[2] Eichmann 1960. The Germans reportedly even made a film during the deportation of the Nagyvárad ghetto that illustrated the brutality of Hungarian gendarmes. In the film, that was later shown to diplomats for propaganda reasons at the German Embassy in Bern, Switzerland, the SS men were obviously not shown. Braham 1997, pp. 646-647.; Lévai 1948, pp. 263-264; Testimony of Samu Stern, Protocol 3627. Copies of the film were lost.

[3] Quoted by Braham 1997, p. 648.

[4] Sztójay's minutes of his talks with Rotta. July 9, 1944. Karsai E. 1967, p. 93.

[5] Sztójay admitted to Rotta that "in some cases and places law enforcement units did display inhuman conduct, but these incidents took place categorically against the government's intentions and the involved units had already been disciplined." Ibid.

[6] Endre Hamvas' letter to Jusztinián Serédi. July 15, 1944. Karsai E. 1967, p. 206.

[7] At the crucial March 29, 1944 meeting of the Council of Ministers Sztójay announced: "his Highness the Regent has given his government free reign in respect to all anti-Jewish measures and he does not intend to exercise his influence in this matter." Quoted by Ránki 1978, p. 241.

[8] Horthy's ordinance to Sztójay. June 1944. Szinai - Szűcs 1965, p. 451.

[9] Horthy's ordinance to Sztójay. June 1944. Szinai - Szűcs 1965, p. 452.

[10] Horthy's letter to Hitler. July 17, 1944. Szinai - Szűcs 1965, p. 468.

[11] Protocol 1859.

[12] Protocol 724.

[13] Protocol 1284.

[14] Protocol 1553.

[15] Protocol 1608.

[16] Protocol 1538.

[17] Protocol 1860.

[18] Protocol 16.

[19] Protocol 2437.

[20] Braham 1997, pp. 565-566.

[21] In Hungarian and international "Holocaust folklore" exercises meant hopping, crouching and running.

[22] Protocol 1970. About the day and its events described by survivors as the "black Saturday," see also Protocol 2930; Protocol 2902; Protocol 2150; Protocol 2 and Lévai 1948, p. 102.

[23] Protocol 3352.

[24] Protocol 1218.

[25] Protocol 2824.

[26] Braham 1997, pp. 565-566.

[27] Protocol 652.

[28] Protocol 1.

[29] A few randomly selected examples from the ghettoes listed above: Ungvár: "All the Jews from around Ungvár were crammed into the city's brick factory. There were a lot of us without space. The SS men beat us and the gendarmerie was even more brutal..." (Protocol 1971); Nagyszőllős: "The gendarmes invented all sorts of tortures, they picked on people and took every opportunity to treat us with extreme cruelty." (Protocol 1359); Beregszász: "We stayed in the Beregszász ghetto four weeks. All our valuable were taken by the gendarmes who beat us all over ..." (Protocol 3308); Huszt: "At the ghetto in Huszt... cadets, gendarmes and the police took turns beating us, using hoe-handles to beat our heads." (Protocol 1350); Iza: "...it was a terrible ghetto, the camp gendarmerie and the SS constantly beat and tortured us." (Protocol 1972); Técső: "During the search the gendarmes made me undress completely to see if I had anything hidden, and they abused me all the while." (Protocol 1110); Sátoraljaújhely: "They treated us terribly at the ghetto, beat us all over searching for valuables everyday." (Protocol 3093)' Máramarossziget: "If they found anyone after 5 p.m. on the street or the courtyard, [the gendarmes and the cadets] took the person to the gendarmerie for a beating." (Protocol 1699); Mátészalka: "The gendarmes beat us for everything, if they came across a Jew on the street by accident, this was enough reason to start the beating." (Protocol 1140); Nyíregyháza: "After three weeks they took us to the Harangodi puszta, ... [in preparation for the deportation, in late April and early May the residents of the Nyíregyháza ghetto were taken to three "pusztas" (a complex of farm buildings)]. More affluent men, my husband among them, were interrogated under terrible blows and torture." (Protocol 2987)

[30] Protocol 1584.

[31] Protocol 2006.

[32] Protocol 3549.

[33] Protocol 1695.

[34] Protocol 3501.

[35] Protocol 2906.

[36] Protocol 3475.

[37] Braham 1997, pp. 739-740.

[38] Protocol 2448.

[39] Protocol 3588.

[40] Protocol 2219.

[41] Protocol 3322.

[42] Protocol 1284.

[43] Protocol 3096.

[44] Protocol 1222. About looting and profiteering by gendarmes see also: Protocol 3400; Protocol 2102; Protocol 3500; Protocol 2374; Protocol 682; Protocol 1804; Protocol 3087; Protocol 348; Protocol 3175; Protocol 1182; Protocol 27; Protocol 19; Protocol 2318; Protocol 2933; Protocol 1620; Protocol 2248; Protocol 38; Protocol 1617; Protocol 3591; Protocol 1691; Protocol 3529; Protocol 3091; Protocol 3420; Protocol 1345; Protocol 1340; Protocol 2241; Protocol 3539; Protocol 3293; Protocol 2959; Protocol 2958; Protocol 3356; Protocol 3477.

[45] Protocol 3351.

[46] Protocol 2590.

[47] Protocol 1530.

[48] "During entrainment people were abused and practically thrown in to the railway cars." (Protocol 2944); "At the Józsefváros railway station we were immediately put on trains, ... the entrainment was accompanied by many blows to the head." (Protocol 2943)

[49] "Two persons tried to escape during the trip. They were shot dead by the gendarmes. (Protocol 2354)

[50] Protocol 3151.

[51] Protocol 1820.

[52] Protocol 2001.

[53] Protocol 2509.

[54] Protocol 1491.

[55] Protocol 2541.

References

Braham 1997

Randolph L. Braham: A népirtás politikája - a Holocaust Magyarországon. (The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary.) Vols. 1-2. Budapest, 1997, Belvárosi Könyvkiadó.

Eichmann 1960

Eichmann Tells his own Damning Story. Life, 1960 November 28.

Karsai E. 1967

Elek Karsai (ed.): Vádirat a nácizmus ellen. Dokumentumok a magyarországi zsidóüldözés történetéhez 3. (Indictment against Nazism. Documents to the History of the Persecution of the Jews in Hungary. 3.) Budapest, 1967, Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete.

Lévai 1948

Jenő Lévai: Zsidósors Magyarországon. (Jewish Fate in Hungary.) Budapest, 1948, Magyar Téka.

Molnár 1997

Judit Molnár: Közigazgatás és Holocaust az V. (szegedi) csendőrkerületben. (Public Administration and Holocaust in the V.th (Szeged) Gendarmerie District.) In Randolph L. Braham-Attila Pók (eds): The Holocaust in Hungary. Fifty Years Later. New York, 1997, Columbia University Press

Ránki 1978

György Ránki: 1944. március 19. (March 19, 1944.) Budapest, 1978, Kossuth.Ságvári 1997

Szinai-Szűcs 1965

Miklós Szinai - László Szűcs (eds.): Horthy Miklós titkos iratai. (The Secret Papers of Miklós Horthy.) Budapest, 1965, Kossuth.