Looting

Plundering Hungarian Jews was a long-standing desire and demand of the antisemites that first appeared in political and intellectual life already at the end of the 19th century. The Numerus Clausus Act of 1920 restricted the Jews' entrance to the universities. Though this discriminative regulation was repealed in 1928, the anti-Jewish laws from 1938 started the gradual exclusion of Jews from intellectual professions, and the confiscation of their property was also initiated. All of this however was not enough for antisemites planning the total plunder and disenfranchisement of the Jews; they demanded the radical solution of the "question". Their time came with the March 19, 1944 occupation of the country as the collaborating Sztójay government realised most of their program in a few weeks: properties and assets of the Jews were frozen by the government, offices and businesses were seized, and their valuables were confiscated. During the ghettoisation and deportation, hundreds of thousands endeavoured to get a share of Jewish wealth.

Click here to read more about the Hungarian Holocaust.

Cavity search and the "mints"

Following the German occupation in March 1944, dozens of decrees were issued to rob of their property Hungarian citizens who

|

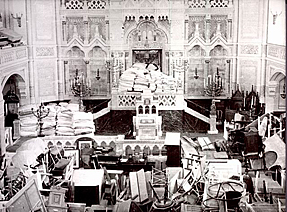

Looted Jewish assets in the Szeged synagogue |

However, prior to ghettoisation, the official decrees issued by the collaborating government did not represent the only threat to Jewish assets. Some members of the gendarmerie did not wait for the start of the state-organised redistribution of wealth and decided to take matters into their own hands, often within weeks following the occupation. In B. S.'s village in Carpatho-Ruthenia gendarmes "entered Jewish homes, they stole and looted, taking all we had".[3] In another village in Carpatho-Ruthenia, "Hungarian gendarmes entered homes and demanded cash and valuables, and those who refused to reveal the hiding place were beaten severely."[4]

On April 7, Minister of the Interior's Secret Decree no. 6163/1944 VII was issued; based on this decree, the ghettoisation of the Jews in Carpatho-Ruthenia started on April 16.[5] In the explanation attached to the decree, the attention of law enforcement officers was drawn to the following: "Special measures must be taken as to prevent Jews from hiding cash, jewellery and other valuables. Therefore, meticulous body searches must be performed not only when they are rounded up, but also when they are transported from temporary collection sites."[6] This part of the decree was executed to the letter.

During the ghettoisation process, Jews who were chased from their homes in minutes and those granted some time to gather their

|

During the ghettoisation process, the gendarmerie wanted to ensure that Jews would leave all the pieces of "national

|

The frenzy for valuables did not abate even after ghettoisation; in fact, it only intensified. Soon, special gendarmerie detective units arrived to uncover hidden Jewish assets. In rooms and basements-called "mints" with utter cynicism-affluent Jews and those suspected to have anything to hide were tortured in large numbers to reveal the location of (alleged) hiding places.

On May 3rd in the Nagyvárad City Hall committees were set up for the recovery of Jewish assets in

|

Gendarmes deporting the Soltvadkert Jews |

The investigative units were to torture the members of local Jewish Councils thinking they, as heads of the

[26] A member of the Council in Salgótarján, lawyer Ödön Szalvendy, was also terribly tortured then was forced to sign a deposition admitting having operated a radio transmitter in his chimney.[27] The brutality of the gendarmes running the "mint" in Salgótarján did not lag behind that of their colleagues in Nagyvárad, Munkács, Kolozsvár, Ungvár and other cities. The 50-strong unit operating in the elementary school also aimed at the soles of their victims, they broke bones and beat four pregnant women almost to death.[28] They covered someone's head with a bag full of horseradish and crushed the breasts of a woman between a door and the door frame.[29] A lawyer was simply thrown out of the window. In the course of a few days sixteen people died at the hands of the interrogators.[30]After the war, a survivor from Párkány recalled that a "mint" was also operated in the Léva ghetto "where detectives beat rich people terribly to confess and reveal the location of hidden valuables."[31] The interrogators at Balassagyarmat were so industrious that even after the Jews were transferred from the city's ghetto to the collecting site at Nyírjespuszta, gendarmerie detectives took some for "interrogation". In the evening, beaten to a pulp, these people were brought back to Nyírjespuszta on carts and automobiles.[32] As recollected by Mrs. Oszkár Weisz, at Nyírjespuszta "one of the detectives visited chief rabbi Deutsch, sat down with legs wide open and said: 'I'm terrible tired, I kept beating all night', then he showed his swollen hands."[33] Mechanic Mór Grünstein gave the following testimony about his days spent in the ghetto at Szamosújvár: "Here the gendarmes started interrogating people, beating wildly. ... If they stopped at night, they continued the next day".[34]

Besides gendarmerie detectives, the rank and file ordered to guard the ghetto parameters also tried to rob as

|

Confiscated Jewish valuables in the synagogue of Szeged |

However, all this was not enough: even in the different stages of deportation (i.e., transport to collecting camps, time spent at these sites and at entrainment) the gendarmes continued to hunt for hidden Jewish assets. During the liquidation of the ghettos all were again subjected to a thorough search, accompanied by the usual abuse. The ghetto at Pestszenterzsébet was liquidated in early July and its population was driven to the collecting camp at Monor. One of the survivors described the events one year later as follows: "On July 1 we were marched to the railway station and put in cattle cars. But first, men and women were searched by the most brutal means. They took about seventy to eighty old people from the nursing home. They took the wheelchair of a paralyzed engineer injured in the first war [WW I] and simply threw him into the railway car. They called a doctor to attend to a woman in labour, but he did not come. She too was thrown into the car and she gave birth there before eighty others where people could barely stand on one foot."[39]

Suffering under terrible hygienic conditions and from lack of food in these detention centres, people

[40] At the Monor collecting site gendarmes interrogated Jews using electricity.[41] In the Szeged brickyard, gendarmerie Captain Imre Finta, head of the investigative unit of gendarmerie district V, and six of his men ordered Jews to give up their valuables or else they would be executed. Eventually Finta and his men found the goods and hauled it away from the brickyard on two flat-back carts to the gendarmerie barracks.[42]Plunder of the deportees

In a mad hunt for hidden valuables gendarmes continued to fleece Jews until the last minutes before deportation, but "the rescue of national assets" did not come to an end even then. The urge to pilfer was strong even during entrainment. For instance, during the deportations in Nagyvárad the gendarmes told people: "if any cash is found, ten Jews will be shot".[43] Similar scenes transpired at the deportation of the Jews from Huszt. A survivor remembered as follows: "Before the train pulled out the gendarmes tried different techniques to rob us more. They selected a man, blindfolded him and forced him to shout that he would be shot if we did not give up all the remaining valuables. If he came to a wagon where there was nothing left to surrender, he was simply shot on the spot."[44] At Kolozsvár Jews received a lesson in patriotism as well: amid a flurry of blows, the gendarmes did not allow Jews to take some of their packages to the cars, saying "you shouldn't give everything to the Germans, leave something for the Hungarians too".[45]

Even after the trains left the station, the gendarmes did not abandon efforts to get at the last, hidden valuables. A woman

|

Assets of deportees on the Birkenau ramp |

Besides threats, there were other ways to get deportees to surrender their remaining cash and other valuables. A survivor from Hajdúböszörmény reported that gendarmes charged Jews who were driven half insane in the scorching summer heat one hundred pengős for a cup of water.[49] Jews deported from Kolozsvár received a pale of water from the gendarmes in exchange for jewellery and fountain pens.[50] The method was particularly favoured among gendarmes deporting labour service battalions from the Józsefváros railway station in late November 1944.

The Hungarian authorities handed over the Jews to the Germans at Kassa. While this usually meant some improved conditions-in most cases the doors were opened and empty water pales refilled-the pillaging did not stop. Mrs M. H. from Northern Transylvania gave her miraculously saved ring to an SS guard to get some water to her young sister who was fainting from thirst.[51] W. M. from Komárom recalled, "during the journey the SS soldiers knocked on the wagon window at every station, saying to hand over all jewellery, cash and underwear still in our possession, or else they would shoot into the train".[52]

The Hungarian Jews lost their last remaining valuables in Auschwitz-Birkenau. They had to leave all their belongings in the cattle car and they got off on the ramp at Birkenau in the clothes on their back. Their luggage was loaded on trucks by inmates of the so-called cleaning brigade (Aufräumungskommando) and carried them to the camp's warehouse complex (BIIg, Effektenlager), better known as Kanada. (The name came from Polish inmates who, during difficult times, imagined the North American country as the promised land. In their black humour they came to call the unfinished camp B.III. "Mexico," since it lacked running water and sewage.)

Dr Mengele and his selecting colleagues sent around eighty percent of arriving Hungarian Jews straight to the gas chambers. Thus, the majority of the deportees were stripped of their last pieces of clothing in the crematoria's dressing rooms. However, the looting still did not end there: before the bodies were consumed by flames, gold teeth in the mouths of the dead were pulled out by members of the "Sonderkommando", which was made up of Jewish inmates. The twenty percent sentenced to life last saw their own clothes in the so-called "Sauna".

For the Jews it mattered little who got hold of their assets. A certain percentage was acquired "illegally" by the Hungarian Gentile population, i.e., they broke into Jewish homes and seized what they could or helped themselves in some other manner to "state assets".[53]

|

Plunder of an evacuated ghetto in the countryside |

References

Benoschofsky - Karsai E. 1958

Ilona Benoschofsky - Elek Karsai (eds.): Vádirat a nácizmus ellen 1. Dokumentumok a magyar zsidóüldözés történetéhez. (Indictment against Nazism. Documents to the History of the Persecution of the Jews in Hungary. 1.) Budapest, 1958, Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete.

Braham 1963

Randolph L. Braham (ed.): The Destruction of Hungarian Jewry. A Documentary Account. Vols. 1-2. New York, 1963, World Federation of Hungarian Jews.

Braham 1997

Randolph L. Braham: A népirtás politikája - a Holocaust Magyarországon. (The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary.) Vols 1-2. Budapest, 1997, Belvárosi Könyvkiadó.

Csíki 2003

Tamás Csíki: Holokauszt Borsod vármegyében. (Holocaust in Borsod County.) New York, 2003, J. and O. Winter Fund - The Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Karsai L. - Molnár 1994

László Karsai - Judit Molnár (eds.): Az Endre-Baky-Jaross per. (The Endre-Baky-Jaross trial.) Budapest, 1994, Cserépfalvi.

Lévai 1948

Jenő Lévai: Zsidósors Magyarországon. (Jewish Fate in Hungary.) Budapest, 1948, Magyar Téka.

Lőwy 1998

Dániel Lőwy: A téglagyártól a tehervonatig. Kolozsvár zsidó lakosságának története. (From the Brick Factory to the Freight Train. The History of the Jews of Kolozsvár.) Kolozsvár, 1998, Erdélyi Szépmíves Céh.

Molnár 1995

Judit Molnár: Zsidósors 1944-ben az V. (szegedi) csendőrkerületben. (Jewish Fate in the V. (Szeged) Gendarmerie District in 1944.) Budapest, 1995, Cserépfalvi.

Munkácsi 1947

Ernő Munkácsi: Hogyan történt? Adatok és okmányok a magyar zsidóság tragédiájához. (How it happened? Data and Documents on the Tragedy of the Hungarian Jewry.) Budapest, 1947, Rennaissance.

Pásztor 2003

Cecília Pásztor (ed.): Salgótarjáni zsidótörténet. (Jewish History of Salgótarján.) Salgótarján, 2003, Nógrád Megyei Levéltár.

Ságvári 1994

Ágnes Ságvári (ed.): Dokumentumok a zsidóság üldöztetésének történetéhez. (Documents for the History of the Persecution of the Jews.) Budapest, 1994, Magyar Auschwitz Alapítvány - Holocaust Dokumentációs Központ.

Tyekvicska 1995

Árpád Tyekvicska (ed.): Adatok, források, dokumentumok a balassagyarmati zsidóság holocaustjáról. (Data, Sources, Documents on the Holocaust of the Jewry of Balassagyarmat.) Annual of the Nagy Iván Történeti Kör. Balassagyarmat, 1995, Nagy Iván Történeti Kör.

Footnotes

[1] Protocol 129.

[2] Protocol 1859.

[3] Protocol 724.

[4] Protocol 1608.

[5] Minister of Interior's Decree no. 6163/1944 BM VII. "On defining the residential area for Jews". April 7, 1944. Benoschofsky-Karsai E. 1958. pp. 124-127.

[6] Published by Karsai L.- Molnár 1994, p. 490.

[7] Ferenczy's report. May 13, 1944. Published by Karsai L.- Molnár 1994, p. 498.

[8] Ruling in the trial of Deputy Police Captain Jenő Borbola. February 18, 1949. Ságvári 1994 (Baranya), p. 28.

[9] Molnár 1995, p. 141.

[10] Protocol 1448.

[11] Protocol 3091.

[12] Ferenczy's report, May 9, 1944. Published by Karsai L.- Molnár 1994, p. 505.

[13] Protocol 1430.

[14] Protocol 3477.

[15] Protocol 1942.

[16] Report by Ungvár Police Captain to the government commissioner of the Carpatho-Ruthenian military zone. Hungarian National Archives I reel 11, p. 56.

[17] Protocol 202.

[18] Gendarmerie order. Ságvári 1994 (Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg), p. 35.

[19] Braham 1997, p. 612.

[20] Protocol 5.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Braham 1997, p. 613. See the list of the names of the detail at the Dreher brewery "mint", ibid.

[23] Lőwy 1998, p. 115.

[24] Csíki 2003, p. 18.

[25] Protocol 151.

[26] Protocol 3005.

[27] Munkácsi 1947, p. 85.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Pásztor 2003, p. 63.

[30] Munkácsi 1947, pp. 84-85.

[31] Protocol 2423.

[32] Protocol 3551.

[33] Protocol 3552.

[34] Protocol 2006.

[35] Protocol 2935.

[36] Protocol 2.

[37] Protocol 516.

[38] Protocol 3475.

[39] Protocol 2248.

[40] Protocol 2448.

[41] Protocol 3322.

[42] Molnár 1995, p. 143.

[43] Protocol 5.

[44] Protocol 38.

[45] Lőwy 1998, p. 197.

[46] Protocol 348.

[47] Protocol 3400.

[48] Lőwy 1998, p. 199.

[49] Protocol 2906.

[50] Lőwy 1998, p. 199.

[51] Protocol 40.

[52] Protocol 27.

[53] A few random examples: when the city government of Kecskemét learned "that some moved into Jewish homes without authorization", the mayor "ordered those moving into Jewish homes arbitrarily to cease occupying the apartments, effective immediately". (Mayor's decree no. 15866/1944, May 24, 1944. Ságvári 1994 /Bács-Kiskun/, p. 58.) In Balassagyarmat, financial officer Sándor Madarász filed charges against eight hundred local residents for the misappropriation of Jewish assets left behind. (Tyekvicska 1995, p. 111.) Due to "frequent break-ins in the ghetto", the Customs and Excise Agency Commissioner of Csorna was forced to order the removal of more valuable Jewish assets into special warehouse. (Report by Jenő Takács, Customs and Excise Agency Commissioner, Csorna. January 13, 1945. Ságvári 1994 /Győr-Sopron/ p. 24.) Of 800 Jewish real estates in Beregszász, the local population burgled and looted 80-100 apartments. (Report by Veesenmayer. June 27, 1944. Braham, 1963, p. 615.) When authorities came to take an inventory of Jewish homes in Munkács they often found the premises cleaned out, moveable goods (e.g., furniture, bed linen, household and personal items) were removed by neighbours (Lévai 1948, p. 102.) In June 1944 the Chief Notary of Huszt complained that "as the Customs and Excise Agency is understaffed, taking inventories and emptying homes will take at least another six months. In that time many break-ins and looting can be expected. Many homes have already been robbed; I report each incident to the gendarmerie but they are also helpless due to the lack of enough men." (Letter of Chief Notary of Huszt addressed to the government commissioner of the Carpatho-Ruthenian military zone. June 21, 1944. Hungarian National Archives I roll 11.)