Labour Service

The labour service system was a special feature in the history of the Holocaust in Hungary. The Horthy regime was averse to admitting communists, members of ethnic minorities and particularly Jews (elements deemed unreliable from the point of view of state security) to the army, the cornerstone of the counterrevolutionary regime. However, it was also loath to exempt these groups from sharing the burden of the national war effort. Therefore, the institution of an unarmed military service, the "auxiliary labour service", was invented. While the labour service claimed tens of thousands of Jewish lives, it cannot be considered part of systematic genocide. Although some officers were determined (and often succeeded) in murdering Jews under their command, the Hungarian state did not set up the labour service system for the wholesale elimination of conscripted Jewish males. The system as a whole cannot be defined as "mobile execution grounds" even if, in practice, certain companies proved to be just that. In an absurd twist, following the German occupation the labour service became a refuge for the doomed; those called up for service escaped Auschwitz-Birkenau. However, towards the end of the war, the Arrow Cross government delivered the majority of servicemen to the Germans who, in the winter of 1944-1945, murdered countless numbers of Hungarian Jews under their command.

Click here to read more about the Holocaust in Hungary.

Labour Service in 1939-1941[1]

The legal foundations of the labour service were laid in Act II of

|

Labour servicemen with national-colour armbands |

The framework developed for organising labour service structures faithfully followed the letter and spirit of the first and second Anti-Jewish Laws. Initially, under stern controls, Jews could serve in the armed forces (while none could serve as full or non-commissioned officers).

In July 1939 nine labour service battalions were organised (each consisting of four companies, thus a total of 7500 recruits) and, in

revisionist successes, pro-German, antisemitic military and political circles gradually gained the upper hand and began to demand with increasing vehemence additional legislation and decrees, which exacerbated the condition of the Jews. As a result, by April 1941, Jewish soldiers lost their right to bear arms and officers were stripped of their ranks. Call-ups were often targeted at specific persons and aimed to achieve propagandistic ends: many prominent Jewish intellectuals and businessmen were enlisted, in some cases in disregard of legal age limits.In this period Jewish labour servicemen were predominantly constructing roads, draining swamps and

|

Labour servicemen resting |

At the end of June 1941 Hungary entered into a state of war with the Soviet Union. In support of the Wehrmacht's military campaign in the Ukraine, 14,413 of the 23,018 conscripts in the nine labour service battalions attached to the "Kárpát group" were Jews (the others were members of the Romanian, Slovak and Serbian ethnic minorities living in Hungary), as well as "politically unreliable" elements (i.e., Communists, Socialists and Jehovah's Witnesses). When the Second Hungarian Army was deployed in the field in early 1942, the antisemitic dispositions of the Ministry of Defence and the political leadership became fully evident. The fate of Jewish servicemen on the Eastern fronts (some 35,000 in September 1942 and approximately 50,000 in the winter of 1942-1943), deprived of army uniforms and forced to wear a yellow armband on their civilian clothes, became extremely precarious. The further companies ordered to the front moved away from Hungary's state boundaries, the more brutal conditions and the guard units of the labour servicemen became. B. P. precisely pointed out this phenomenon in his testimony: "We were escorted by the same guards, but they treated us in a completely different way when we were outside of the limits of the country. Those who were the most decent to us in Hungary were hitting and abusing us in Russia." [5]

Given meagre supplies,

|

Grave of a labour serviceman on the Eastern Front |

Not all Hungarian soldiers treated the labour servicemen brutally. Many of them - from the highest levels to the rank and file - behaved in a humane way. Colonel General Vilmos Nagybaczoni Nagy, the new Minister of Defence replacing the pro-German Károly Bartha in September 1942, intended to make radical improvements in the lot of labour servicemen. At least within Hungary in areas under his direct control, his attempts were partly successful. However, even his best efforts failed as many of his orders were sabotaged by the ministry's antisemitic staff officers, and under his tenure decrees were issued implementing Act XIV of 1942 enacted on July 31, 1942, a compendium of discriminative directives regulating the labour-service system. Nagy was forced to resign when, in the summer of 1943, he rejected the German demand that Hungary provide servicemen to work the copper mines in Bor, Serbia.

Following the Russian military breakthrough at Voronezh in January

|

Minister of Defence Vilmos Nagybaczoni Nagy visits a labour service unit in 1942 |

Some among the retreating German and Hungarian armies took their revenge on starving and freezing servicemen who were exhausted to the breaking point. In the chaos that ensued after the military collapse, on many occasions Germans forced Hungarian troops to evacuate warm and dry quarters, and Jews had little chance to find food and shelter. Many starved or froze to death; others were overcome by a variety of diseases. Mass murders took place as well. On April 30, 1943, near the Ukranian village of Doroshich, Hungarian soldiers padlocked and set on fire an infirmary barrack housing servicemen suffering from typhoid fever. Those who managed to leap from the burning inferno were gunned down. Around 800 labour servicemen died in this incident alone. Photographer Ignác Braun was among the survivors: "The doors and the windows were closed, so that we would not be able to get out. When with great efforts we could open some of them, many people wanted to get out at once, so we were on top of each other: it was such a bedlam. People were treading on each other. Burning people were running out of the building just to face machine-guns waiting for them outside. I could get out only with burns, which later got healed."[9]

The reorganised Hungarian army (which the Hungarian military and political elite was loath to send into combat again) was redeployed as an occupation force on the Eastern front. By the summer of 1943, additional twenty labour companies were directed to support the occupation army. That summer the first labour companies also arrived in the copper mines of Bor, Serbia.

The German occupation of Hungary on March 19, 1944 created a new situation for the country's labour service system as well. After the organisation of thirty-one new companies, Prime Minister Döme Sztójay had offered the Germans another 50,000 slave labourers. The ghettoisation of Jews in the countryside was under way, to be followed by mass deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau on May 15. Paradoxically, even as overall conditions in the labour service deteriorated, this time labour service became a refuge and call-ups meant that thousands of men escaped the gas chambers. On many occasions, the Ministry of Defence delivered call-up notices even in ghettos and collection centres, arousing the anger of the gendarmerie and the Germans. The change of heart in 1944 on the part of many previously firmly pro-German and antisemitic Ministry officials and staff remain unclear to this day. It is evident, however, that by that time both the Ministry and the government were motivated to keep the Jewish workforce inside the country, and some public officials used this pretext to save the lives of Jewish citizens.

In the days immediately preceding the Arrow Cross coup d'état,

|

Arrow Cross militiamen |

The Szálasi government "lent" a percentage of Jewish men between 16 and 60, and women between 16 and 40 to the German authorities. Under an agreement, not only recently recruited, but all labour service companies were ordered to move to western Hungary. By December 1944 some 30,000 Jews from Budapest were marched toward Germany and additional thousands of labour servicemen were handed over to the Germans to build new defence lines in the border region. Active servicemen on forced marches to these positions were treated with equal brutality, as were deportees from Budapest. J. K. of Budapest was dragging himself in one of these columns: "We were escorted by Arrow Cross men, who behaved more brutally than the SS. When we arrived in Csomád 4 days later we had already had casualties, as the Arrow Cross men shot dead a few men. Before our departure they had tortured us. We were tired, hungry and psychically tormented." [11] Tibor Braun was also a participant of the death marches: "We were lying in the football field in Dorog in mud and pouring rain. Whoever wanted to stand up or just raised his head at night so as not to lie in the mud was beaten with a butt of a rifle."[12]

In the labour camps on the western border several thousands fell victim to disease, hunger and the cruel treatment at the hands of their captors. The majority of survivors were driven on toward west. Those struggling to keep up, leaving the column or bending down for a scrap of food were shot on the spot. "We were thirty-five kilograms apiece, human wrecks who were not afraid of death. We were ready to jump out of the row for a slice of potato under ripple fire and we did not care about it" - remembered R. K., a locksmith from Pestszenterzsébet.[13] The survivors of these death marches ended up in the camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Günskirchen and Bergen-Belsen, where countless more thousands perished.[14]

Labour Camps in Bor, Yugoslavia

With the 1941 invasion of Yugoslavia the Germans acquired large copper mines

|

The copper mines of Bor |

The labour force at Bor was housed in eight camps around the mines. The camps were under the control of the Hungarian army, and work in the mines was supervised by armed members of the German paramilitary work organisation, the Organisation Todt. While conditions varied slightly from camp to camp, treatment and accommodations for servicemen were acceptable on the whole until the end of 1943. However, when Lieutenant Colonel Ede Marányi took over as commander of the camps, beatings, truss-ups and executions became routine. "We had good times under the command of Lieutenant Colonel András Balogh. However, he was replaced with Marányi in December, under the command of whom our life turned unbearable. We were regularly tortured, beaten and trussed up ... Warrant Officer Pál stated several times: 'No Jews will return home from here'." -testified József Goldschmied, a butcher from Kapuvár, after his liberation.[15]

In September 1944, due to the deteriorating military situation, the Germans decided to evacuate the mines. Servicemen were ordered to move north in two waves.

Words of the survivors - link centerA person who you would call a real Jew-killer They indulged in their bestial sadism and antisemitic hatred against us |

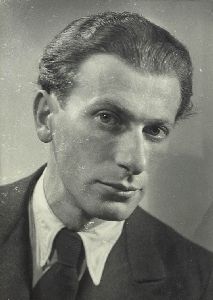

|

Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti |

Survivors of the first Bor contingent were marched on from the western border towards the interior of the collapsing Third Reich, to the camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen and Flossenbürg. The second group that set off from Bor at the end of September fared much better. Soon after leaving, the convoy was attacked by Yugoslav partisans. They executed the most bloodthirsty Hungarian officers and soldiers on the spot and the servicemen were set free. Some of them joined the ranks of the partisans. Merchant Gyula Vészi was lucky enough to be in the second contingent and was liberated by the partisans: "Warrant officer Torma departed from this life five minutes later. Then we selected a few people from among the guards who had behaved decently towards us. We gave them prisoner clothes with stars and took them with us. The rest were executed by the partisans on the spot."[17]

Footnotes

[1] On the labour service in detail see Braham 1997, pp. 287-370.

[2] Protocol 2093.

[3] Protocol 2092.

[4] Protocol 1844.

[5] Protocol 3013.

[6] Protocol 670.

[7] Protocol 2137.

[8] Protocol 1528.

[9] Protocol 875.

[10]Protocol 3006.

[11] Protocol 3038.

[12] Protocol 1638.

[13] Protocol 2348.

[14] On the history of the labour service during the Arrow Cross rule see Szita 1989 and Szita 1991.

[15]Protocol 2064.

[16]Protocol 841.

[17]Protocol 3603.

References

Braham 1997

Randolph L. Braham: A népirtás politikája - a Holocaust Magyarországon. (The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary.) Vols. 1-2. Budapest, 1997, Belvárosi Könyvkiadó.

Szita 1989

Szita Szabolcs: Halálerőd. A munkaszolgálat és a hadimunka történetéhez 1944-1945. (Death Fortress. Data on the History of the Labour Service and the War Labor 1944-1945.) Budapest, 1989, Kossuth.

Szita 1999

Szita Szabolcs: Utak a pokolból. Magyar deportáltak az annektált Ausztriában 1944-1945. (Roads from Hell. Hungarian Deportees in Austria 1944-1945) Budapest, 1991, Metalon Manager Iroda KFT.