The First Massacre: Kamenets-Podolsky

As opposed to the European Jewish communities destroyed by the Nazis, the majority of Hungarian Jews were not in life danger until the spring of 1944. Nevertheless, between 1941 and 1944 Hungarian Jewry suffered losses that can be measured in the tens of thousands.

The Hungarian government, which stepped onto the path of institutionalised antisemitism by creating consecutive anti-Jewish Laws from 1938, was utterly frustrated by the fact that

|

Miklós Kozma, initiator of the deportations |

The new Hungarian authorities of Carpatho-Ruthenia, which was occupied in 1939, were bothered by more than one element of the presence of the Jews: they outnumbered the Hungarians; a large part of the community consisted of the conservative, religious, orthodox Jews despised by the new rulers; and there were many foreign refugees among them. The thought of deporting the poor, rural Jewry occurred to the government commissioner of Carpatho-Ruthenia, Miklós Kozma, already in the fall of 1940.[1] In the winter of 1940-1941 in the framework of arbitrary "cleaning" actions, Jewish families were driven across the Soviet and Romanian borders at some places by the Hungarian civilian and military authorities.[2] The next spring Hungarian authorities expelled plenty of Serb inhabitants from the re-annexed Délvidék (Southern Provinces), since they considered them hostile. Meanwhile Kozma carried on planning to deport the rural Jews. A possibility for that opened up in the summer when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Leaders of the army, the public administration of Carpatho-Ruthenia and some officials of KEOKH supposed that under the chaotic circumstances of war they could deport the unwanted Jews to no man's land. Kozma gained the approval of Prime Minister László Bárdossy, Minister of the Interior Lajos Keresztes-Fischer and also Regent Miklós Horthy. The round-up of the "stateless" Jews (i.e., those who were not holding Hungarian citizenship) and the Jews with "unsettled citizenship" commenced in July. The objective of the action was "to move as soon as possible the largest number of Polish and Russian Jews, who have infiltrated the country lately". According to the explanation, those deported would have stayed under Hungarian control, since Hungarian troops were occupying Galicia. Jews were also promised to obtain the real estates of those Jews who left the territory with the retreating Red Army. This cynical lie was only a cover for looting the victims: Jews deported from Hungary were allowed to take only 30 pengős, food for three days and some personal belongings.[3]

Round-up and deportation

Hungary and the Soviet Union entered a state of war at the end of June 1941. The round-up of the Jews

|

Jews deported from Hungary in 1941 |

Abuse of authority was widespread during the action. Only eight Jewish families lived in Eötvösfalva. All of them were Hungarian citizens, still they were deported. 18-year-old Hanna K. was visiting relatives in the neighbouring village, Taktaharkány. Returning home, she found the Jewish homes vacant. Hanna never heard from her parents or neighbours again. She escaped to her relatives. In 1944 they were deported to Auschwitz together.[6] From Alsószinevér, approximately 300 people were deported-mostly merchants and farmers.[7] Izsák Jakubovics married in Silesia. When the Nazis invaded Poland, he escaped with his family to the Carpatho-Ruthenian village of Majdanka, which he thought was safe. As Polish Jews, they were deported across the border in 1941, but many other Jews from Majdanka-including Hungarian citizens-were dragged off as well.[8]

The Hungarian authorities were rounding up Jews not only in Carpatho-Ruthenia, but also in

|

Victims of the Kőrösmező deportations |

A majority of those rounded-up was transported to the collection camp set up at the border station of Kőrösmező. As a foreshadowing of the 1944 deportations, cattle cars and truck convoys arrived there and left for Galicia and Ukraine. The first transport left on July 14. In the following weeks 13,400 Jews from Carpatho-Ruthenia and 4000 Jews from the rest of the country were deported across the border. The transports headed northeast, but the destinations were different.

Massacre at Kamenets-Podolsky

Most of the deportees were taken to Kamenets-Podolsky through Kolomea. With the retreat of the Soviet

|

Picture on the preparations of the execution made clandestinely by a Jewish driver. |

The fate of the other deportees

Based on the recollections of the survivors, it is clear that only a part of the deportees were taken

|

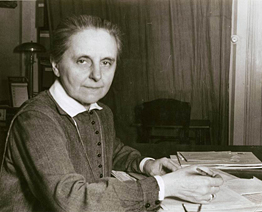

Margit Slachta |

For the majority, ordeals started after crossing the border. The unfortunate deportees were at the mercy of not only the Hungarian and German armed forces, but also of the collaborating Ukrainian militia and the local inhabitants: "One time Hungarian, another time German soldiers beat them, elderly people were either shot or thrown into the Dnester River. They shot my mother in front of my brother who managed to come back from death's door." - as the story was told by one of the Schächters, a girl who was the only family member remaining home.[20] Hermann Frimmer, a labour servicemen from Tiszaújváros, witnessed how the Hungarian soldiers heading to the front cruelly treated the Jewish deportees: "A sergeant of Nyíregyháza Jenő Király had 17 people thrown into the Dnester in front of our eyes, people deported from Hungary in 1941. Amongst them there was a married couple I knew."[21]

A 17-year-old-boy, arrested in Budapest, was deported with his family: "They crossed the borders with us and then let us free, telling us to go wherever we wanted to. We crossed the Polish border at Kőrösmező, we could not turn back as they would have killed us but could continue in the direction of the centre of the country. In Poland we went into a forest where the SS and Hungarian gendarmes were shooting at us. Unfortunately, I saw how they shot my mother and my brothers and sisters." After that the boy escaped back to Hungary alone.[22]

Thousands of deportees managed to get to Stanislawow. The Ukrainian population attacked the Jews already after the Red Army left, but the Hungarian army thwarted the pogrom. The mass killings commenced when at the end of July the Germans took control over the city. This period was remembered by Adlers from Alsóapsa: "The major part of the deported Jews were shot, some were taken into the ghetto of Stanislawow. They threw many into the river Dnester, cut the breasts of women, cut children into two and buried a lot of people alive."[23] Those still alive in March 1943 were sent to the gas chambers of the Belzec extermination camp.[24]

The members of the Sachs family arrived at Chortkow, as did many other deportees. In spite of the warnings

We were in a horrible state of mind and had no idea what would happen to us ...The day after the people who stayed in barracks (around 4,000 of them) had to start marching on foot. They were chased for 10 days in rain and mud when the Gestapo killed them. Eight of them survived."[25]

The events of the 1941 deportations that took place over the border can be reconstructed from the recollection of those survivors who managed to get back to Hungary. Most of them paid Polish, Hungarian or Ukrainian peasants for help: they showed the way through the passes of the Carpathians, they hid the Jews in their wagons. Many Jews made their way back home in Hungarian military vehicles; the soldiers hid the escapees on the flatbeds of their trucks or in the trunks of their cars for money or from regret.

End of the deportation

In August 1941, yielding to German demands, the Hungarian government temporarily halted the deportations. In addition to

[26] Soon the Hungarian government was informed about the massacres. In November 1941, Prime Minister László Bárdossy informed the Lower House that they wished to carry on with the deportations, "but the amicable German Reich warned us not to do so".[27] Out of the approximately 18,000 deportees, at most 2000 to 3000 managed to make their way back to Hungary. About 15,000 to 16,000 of the deportees were buried in the mass graves of Kamenets-Podolsky, Stanislawow, Chortkow and or thrown into the gas chamber of the Belzec extermination camp.

Footnotes

[1] Ormos 2000, pp. 728-737.

[2] For a summary of the topic, see Kádár-Vági 2005, pp. 72-73. In detail see Tibori Szabó 2004, pp. 115-123.

[3] Braham 1997, pp. 199-202.

[4] Protocol 129.

[5] Protocol 2830.

[6] Protocol 228.

[7] Protocol 588.

[8] Protocol 2767.

[9] Protocol 2067.

[10] Ormos 2000, pp. 762-763; Braham 1997, p. 203.

[11] Ungváry 2005, pp. 177-178. See also protocol 447.

[12] Operational Situation Report USSR No. 66. August 28, 1941. Arad-Krakowski-Spector 1989, p. 112.

[13] Hilberg 1985, p. 812.

[14] Braham 1996, pp. 15-16.

[15] Protocol 447.

[16] Braham 1996, pp. 16-17.

[17] Protocol 651.

[18] Protocol 699.

[19] Protocol 1097.

[20] Protocol 2830.

[21] Protocol 447.

[22] Protocol 748.

[23] Protocol 129.

[24] Pinkas Hakehillot Polin, pp. 368-372.

[25] Protocol 2067.

[26] Braham 1997, p. 205.

[27] The information on the fate of the deported Jews reached the Minister of the Interior in August, and Government Commissioner of Carpatho-Ruthenia Miklós Kozma in October at the latest. Ormos 2000, pp. 763-767.

References

Arad-Krakowski-Spector 1989

Yitzak Arad-Shmuel Krakowski-Shmuel Spector: The Einsatzgruppen Reports. Selections from the Dispatches of the Nazi Death Squads' Campaign Against the Jews in Occupied Territories of the Soviet Union July 1941 - January 1943. New York, 1989, Holocaust Library-Yad Vashem.

Braham 1996

Randolph L. Braham (ed.): A magyarországi háborús munkaszolgálat. Túlélők visszaemlékezései (Labour Service in Hungary. Survivor Recollections.) (TEDISZ, 1996, Budapest

Braham 1997

Randolph L. Braham: A népirtás politikája - a Holocaust Magyarországon. (The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary.) Vols. 1-2. Budapest, 1997, Belvárosi Könyvkiadó.

Hilberg 1985

Raul Hilberg: The Destruction of the European Jews. Vols. 1-3. New York-London, 1985, Holmes and Meier.

Kádár-Vági 2005

Kádár Gábor-Vági Zoltán: Hullarablás. A magyar zsidók gazdasági megsemmisítése. (Robbing the Dead. The Economic Annihilation of the Hungarian Jews.) Budapest, 2005, Jaffa-HAE.

Ormos 2000

Ormos Mária: Egy magyar médiavezér: Kozma Miklós. (A Hungarian Media Tycoon: Miklós Kozma.) Vols. 1-2. Budapest, 2000, Polgart.

Pinkas Hakehillot Polin

Pinkas Hakehillot Polin - Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland. Volume II (Ukraine). Coordinated by Joyce Field. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/Pinkas_poland

Tibori Szabó 2004

Tibori Szabó Zoltán: Csík vármegye zsidósága a betelepüléstől a megsemmisítésig. (The Jewry of Csík County from the Settlement to the Annihilation.) In Randolph L. Braham (ed.): Tanulmányok a holokausztról 3. (Studies on the Holocaust 3.) Budapest, 2004, Balassi. Pp. 103-142.

Ungváry 2005

Ungváry Krisztián (ed.): A második világháború. (The Second World War.) Budapest, 2005, Osiris.