A City in the Countryside: Balassagyarmat

Balassagyarmat was home to a flourishing Jewish community in the decades prior to the Holocaust. Its communal, religious and intellectual life was rich and vibrant. The destruction of the Balassagyarmat Jews is a typical case of what was happening to the Jews of the cities of the Hungarian countryside in the spring and summer of 1944.

Click here to read more about the Holocaust in Hungary.

The Jews of Balassagyarmat[1]

The first Jews arrived in Balassagyarmat

|

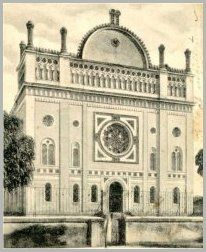

The Balassagyarmat synagogue before 1944 |

The Jewish community of Balassagyarmat increased more or less steadily (with minor stops and fallbacks) until the 1920s. Its population reached its peak in 1920 (at 2245). From then on the vital statistics show a decreasing tendency: in 1930 there were 2013, and in 1941 only 1712 Jews in the city. In addition, sixty-one Christian inhabitants of Balassagyarmat were declared to be Jewish by the discriminatory anti-Jewish laws. In April 1944 the Orthodox congregation consisted of 1516 members; it was presided over by broom factory owner Mihály Lázár. The rabbi serving as a registrar of vital statistics was Dávid Deutsch, a descendant of the Deutsch family that had led the liturgical life of the Balassagyarmat congregation for decades. The relatively wealthy community operated five institutions: the Chevra Kadisa (burial society), Jewish Women's Association, Bet-hamidros Association (temple society), Girls' Youth Charity Association and the Jewish Girls' Association. Besides these a congregational foundation (Zsigmond Ungár - Zsófia Fröhlich Foundation for the Home for the Aged) was also active in Balassagyarmat. When preparing the ghettoisation process, the Hungarian authorities planned on concentrating 1780 Balassagyarmat Jews, i.e., the number of Neolog (non-Orthodox) Jews and Christians defined as Jews by the anti-Jewish laws must have been around 250.

The Jewry of Balassagyarmat was predominantly

|

Postcard from the 1900s. The synagogue is on the right, the Catholic church is on the opposite side |

Beginning of the persecution

The discriminatory legislation prior to 1944 caused significant damage to the Jews of Balassagyarmat. For example, Act XV of 1942 stipulating the confiscation of Jewish-owned agricultural real estates was implemented more strictly than was customary across the nation; as a result many Balassagyarmat Jews lost their pieces of land.

Initiated by the local authorities, the widely respected president of the congregation Oszkár Weisz was interned in 1942 and later-despite his heart condition and his age 48 years-he was called up for labour service in Ukraine. According to the testimony of his wife, Weisz was arrested "on the absurd plea that 'he might have a bad influence upon the public in the upcoming era'. There was not chance to appeal"[3] (Weisz came home from Ukraine and he was interned again on May 1, 1944. He was taken to the Mosonyi Street detention facility, then to Nagykanizsa and from there to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he was killed).[4]

Due to the proximity of the Hungarian-Slovakian border, Balassagyarmat became a transit station for Jews escaping from Slovakia before 1944. In 1942-1943 many illegal refuges arrived in the city, several of whom were arrested and imprisoned in Balassagyarmat.

Ghettoisation[5]

The ghettoisation process in Nógrád County took place between May 5 and 10, 1944. Sometime around the end of April or the beginning of May, Gendarme Colonel László Ferenczy, who directed the operations locally, hosted a meeting in the Ministry of the Interior with regard to the ghettoisation. Among the participants were Prefect of Nógrád County József Baross and commander of the Balassagyarmat police László Eördögh. After being briefed by Baross on the orders given at the meeting, Sub-prefect Sándor Horváth called together the mayors and chief constables of the county by May 2. The participants of the meeting elaborated on the details of the ghettoisation schedule of the Nógrád Jews. The plan designated the following collection points: Losonc (for Jews of the city Losonc, Losonc and Szécsény District), Balassagyarmat (for Jews of Balassagyarmat, Balassagyarmat and Nógrád Districts), Salgótarján (for Jews of the city of Salgótarján and Szirák District) and Kisterenye (for Jews of Kisterenye and Salógtratján District). The deadline of the implementation was set for May 10.

The setting up of the Balassagyarmat ghetto was directed by the mayor of the city, Béla Vannay. The details of the border creation were consulted on with the members of the local Jewish Council too, which had been established

|

Chief Rabbi Dávid Deutsch in front of the synagogue. He was killed in Mauthausen |

The order inside the ghettos was maintained by the Jewish police consisting of thirty people and led by Pál Sándor and András Fleischer. Police Chief László Eördögh did not have the personnel to safeguard both ghettos; therefore he asked for reinforcement from his superiors on May 15. On May 18 the custody of the large ghetto was taken over by a unit of sixty gendarmes redeployed from Miskolc, led by a certain Gendarme Captain Bretány (or Bretany, Bretán). The small ghetto was guarded by the local police during its whole existence. Shortly, gendarme detectives arrived from Miskolc, who set up their headquarters in 15 Kossuth Lajos Street. Using the same brutal methods that were common throughout the country, they interrogated wealthy or supposedly wealthy Jews about the alleged hiding places of their valuables. Mrs. Weisz "escaped beating, because I told them immediately where I had hidden my valuables".[6]

The ghettos were overcrowded: on average, eight to ten people were crammed into one room. Soon the danger of a typhoid fever epidemic emerged; therefore the authorities-pressured by director of the local hospital Dr. Albert Kenessey-ordered compulsory vaccination. It had to be performed by Jewish physicians and the vaccine was paid for from confiscated Jewish wealth.

The reactions of the Gentile population of Balassagyarmat

|

Tea party of Jewish and Christian children in the 1930s |

The ghettoised Jews of Nógrád County-as in many other regions of the country-were helped by the Ministry of Defence in the last minute before the deportation by sending summonses to report for labour service. From the Balassagyarmat ghettos ca. 300 men between the ages of 16 and 48 were called up for labour service. This way they escaped deportation to Auschwitz. By the request of Military Work Centre no. 672 of Salgótarján, women were also dispatched out of the ghetto to perform agricultural work, but later they were taken back. As Mrs. Weisz put it: "We generally thought we would get away with it [with the agricultural work] . Unfortunately, we could not be under that delusion too long. We could feel there was something in the wind."[9]

Deportation

As part of Gendarmerie District VII, Nógrád County was part of Deportation Zone III.

Words of the survivors - link centerThey were beating people mercilessly They tried to extort the secrets of the poor victims by exquisite torture |

The sheds were guarded by gendarmes who did not cease to drag away Jews to the interrogation centre in 15 Kossuth Lajos Street. According to Erzsébet Schenk, those taken away were usually carried back to Nyírjespuszta on carts, since most of them were unable to walk due to the torments they had suffered.[12] "One of the investigators came to visit chief rabbi Deutsch and told him 'I am so tired, I was beating people all night' and he showed him his swollen hands," remembered Mrs. Weisz.[13]

The prisoners of Nyírjespuszta and Illéspuszta were deported to Auschwitz on two transports dated June 10 and 12. First they were driven to the Balassagyarmat railway station where they were crammed into cattle cars brutally, which was a common occurrence in the entire country. The trains were departing here for Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Approximately 800-900 Jews were sent immediately to the gas chambers by Dr Mengele on the ramp. He found ca. 400-450 women and 150 men capable of working, of whom 60 women and two men returned to the city after the war. Of the ca. 300 men called up for labour service in 1944, 120 returned. It is not certain that all of those who did not return had been killed, but even if we consider this factor, we can estimate the rate of loss of Balassagyarmat Jewry at 80-90 percent. In 1949 the Orthodox Jewish community consisted of 228 members.

Covering up the traces of the Jews

The abandoned houses of the Jews were

|

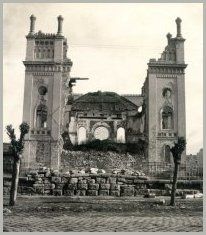

The ruins of the synagogue |

Footnotes

[1] For the data and information regarding the Jewish community of Balassagyarmat before the Holocaust, see Szederjesi-Tyekvicska 2006, pp. 334-338.

[2] Protocol 3550.

[3]Protocol 3552.

[4] Szederjesi-Tyekvicska 2006, p. 344.

[5] For the ghettoisation and deportation of the Balassagyarmat Jews in detail, see Szederjesi-Tyekvicska 2006, pp. 27-90 and Braham 2007, pp. 770-772.

[6] Protocol 3552.

[7] Protocol 3551.

[8] Protocol 3550.

[9] Protocol 3552.

[10] Protocol 3551.

[11] Protocol 220.

[12] Protocol 3551

[13] Protocol 3552.

[14] Tyekvicska 1995, p. 111.

[15] Szederjesi-Tyekvicska 2006, p. 348.

References

Braham 2007

Randolph L. Braham (ed.): A magyarországi holokauszt földrajzi enciklopédiája. (The Geographic Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust in Hungary) Vols. 1-3- Budapest, 2007, Park.

Szederjesi - Tyekvicska 2006

Cecília Szederjesi - Árpád Tyekvicska: Senkiföldjén. Adatok, források, dokumentumok a Nógrád megyei zsidóság holocaustjához. (In No Man's Land. Data, Sources and Documents on the Holocaust of the Nógrád County Jews) Balassagyarmat - Salgótarján, 2006, Studium Libra - Nógrád Megyei Levéltár.

Tyekvicska 1995

Árpád Tyekvicska (ed.): Adatok, források, dokumentumok a balassagyarmati zsidóság holocaustjáról. (Data, Sources, Documents on the Holocaust of the Balassagyarmat Jews.) Nagy Iván Történeti Kör évkönyve. Balassagyarmat, 1995, Nagy Iván Történeti Kör.